A Total Solar Eclipse

To know why, we must go back to the 19th of June 1936, the day of a total solar eclipse, which caused a band of darkness to circle the globe, a village on the Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido, where a renowned Cambridge University astronomer, FJM Stafford, adjusted his telescope to view the adjacent island of Iterup, 200 nautical miles distant, the first of the islands that arc from Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido to Russia. And while Professor FJM Stafford, Colonel in the Royal Corps of Signals, brilliant mathematician, astrophysicist, hero of the First War, might have chosen any other site, in Inda, Australia, or elsewhere, chosen the isolated village of Karishimi in the north Japanese island of Hokkaido…. For one, recent developments in the Pacific that were of deep concern to Briain, Japan’s 1931 invasion of Manchuria, installing a puppet Chinese emperor, making it an imperial possession. Posing a threat to the British Empire in the Pacific, notably Malaya, Singapore, Burma, India, along with Australia and New Zealand; France’s Indochina of Vietnam and Laos And two otial traffic the British Government, military services and special services. Traffic the security of which was essential to the security of Britain. One professional, that led him to Hokkaido, and the remote village of Karishimi, for his astronomical ministrations. had one other quality, never publicly displayed, spy. Not a common every-day lurker, a gentle, modest radio and generous man, with little self-interest, but endowed with very-exceptional powers of intellect and – tested in war – courage. Someone to rely on. In April 1940 (verify year), he arrived in Ottawa and, accompanied by Captain Ed Drake, then Assistant Director of the Canadian Army’s MI2, arrived at the Examination Unit, Canada’s then civilian signals intelligence (SIGINT) organization, in a house at 245 Laurier Avenue in Ottawa, beside the residence of Canada’s Prime Minister’s, Mackenzie King. A singular fact of which Japanese authorities were quite unaware.

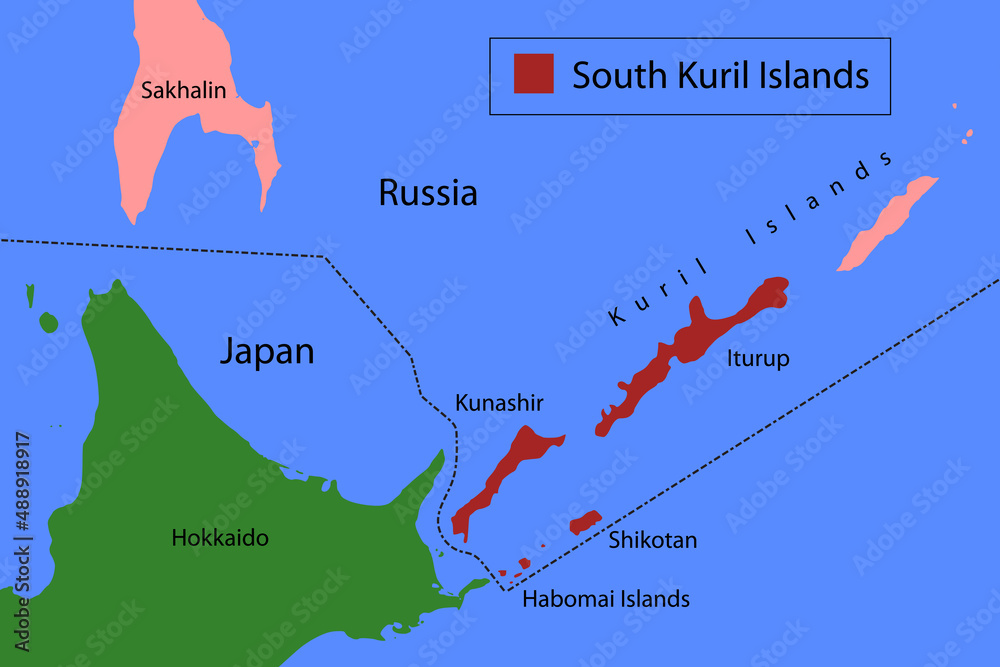

A village that overlooked the Island of Iterup

The Pearl Harbor story began several years earlier, even before the day of a total solar eclipse, 19 June 1936, the village of Kamishari, on the Japanese Home Island of Hokkaido. Where FJM Stafford, Cambridge University Fellow, professor of astrophysics, member of the Royal Corps of Signals (RCS), radio intelligence specialist in the First War, and radio intelligence specialist in the Second, who led the expedition to observe the local characteristics of the event, managed the entire worldwide astronomical expedition, with teams from Russia, India, Australia and Japan, to name just a few, and with the members of his team, set up their telescopes and related instruments. Stafford was so keen that, wanting a particular site for his observations, asked the Japanese astronomer who had initially taken the spot, to exchange places. Which the kind Japanese professor agreed. The observation post was special for Stafford, odd given that, as astronomers, there professional concern would be thought to be the heavens, not below. Whatever the case, the spot chosen happened to overlook, 200 nautical miles distant, the first major island of the Kuriles, Iturup. And Hitokappu-Wan, the bay from which, two-and-one-half years later, Kido Butai would gather, then, on the morning of 26 November 1941, set sail for the island of Oahu, Hawaii, and the attack on Pearl Harbor. At that point it time, Stafford would be in Ottawa, as close associate, scientist and assistant to Captain Drake, then the Director of MI2. So close that Stafford and Drake shared the same office.

Professor Stafford would occasionally leave his telescope to walk to the heights overlooking Iturup island 200 nautical miles distant, holding a hand-held optical instrument that he would look through to make a personal, quite confidential, observations. Likely an observation of ionospheric conditions, which happen to be especially important for radio intercept of direction finding, and interception of messages from marine vessels.

He was assisted by a half-a-dozen men from the British Embassy in Tokyo, recently arrived from Britain, who by the evidence, to be later discussed, were members of SIS (Special Intelligence Service).

There were two other aspects of Cambridge FJM Stafford of interest. In 1939, shortly after the commencement of the war, British authorities feared the possible presence of German spies, collecting intelligence for a possible German invasion of Britain, and sending the intelligence to Germany over radio. Stafford became one of three who set up a team to search and locate such activity, employing radio intercept means. It was run by GC&CS, and was known, informally, as ISOS (Intelligence Service Oliver Strachey), after the name of one of the three, Oliver Strachey. Strachey, like Stafford, a brilliant mathematician, but also a very capable cryptanalyst, with a particular developed interest in machine decryption. In particular, machine decryption of high-level Japanese cyphers. He later became expert in the Japanese language, to augment his capacity with French, German, Italian, and, or course, English.

The third man in the GC&CS team was Alastaire Denniston, who had created and headed GC&CS. In Ottawa, the three, Strachey, Strafford, and Denniston, lived in the same residence. Their discussions, including those with Ed Drake, Director of MI2, certainly were among the most secret discussions of the Second War.

each was Director of the Examination Unit. Strachey, Stratton and Denniston were at times Director of the Examination Unit, and all three, including along with Captain Edward Michael Drake, Director of MI2, were members of Canada’s “Y” Committee, which oversaw the activities of Canadian radio intelligence. To a large extent, GC&CS was the dominant actor that was MI2. But the day-to-day operations were in the hands of MI2 Director, Captain (then Colonel), Ed Drake.

Operations for which were added three sets of quite specialized equipment, for recording the technical characteristics of radio messages, therefore to identify the equipment, and, therefore, the vessel.

[i] Astronomical Physics. By F. J. M. Stratton. New York, E. P. Dutton and Company. 1926